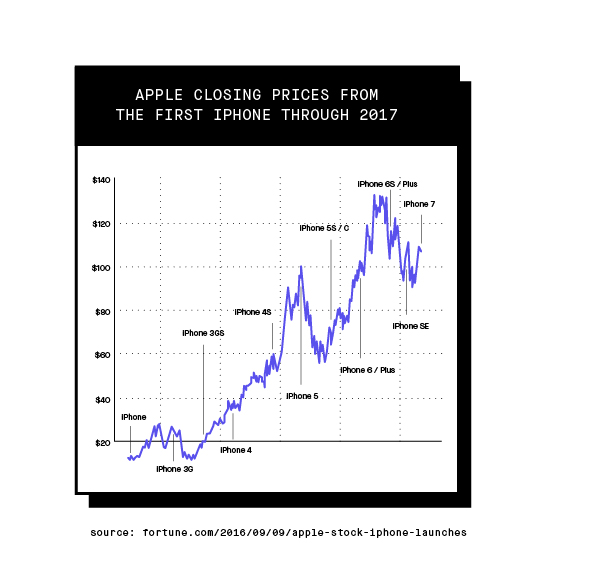

On June 29, 2007, Apple introduced the first generation of iPhone, and transformed the way the world communicates.

Ten years later, with two billion iPhones sold worldwide, Apple is one of the world’s most valuable companies, with an estimated market cap of nearly one trillion dollars.

The success of the iPhone doesn’t come down to luck, or being in the right place at the right time. Instead, Steve Jobs and his team used perfectly executed product design to rethink what we could expect from a handheld phone.

From video streaming services like Netflix to search engines like Google, our world is filled with examples of brilliant product design—the best of which lead to products that can be hard to imagine life without. In a nutshell, product design is building digital products to solve problems. To understand how and why it really works, however, we need to go all the way back to the late 19th century, and the emergence of a new field called ‘industrial design.’

Centuries before the term ‘product design’ became part of the tech lexicon, the field that described designing products for people was called industrial design. From cars to chairs, almost any product—or at least any good product—looked and worked a certain way based upon the decisions made by an industrial designer.

Henry Dreyfuss was one of America’s first prominent industrial designers. In his 40 year career, he designed countless products like the Hoover vacuum and the Polaroid camera. And unless you were born after the year 2010, chances are you probably had one of these thermostats—a Dreyfuss product—in your home.

Around the 1950s and 1960s, a revolution took place within industrial design. Before this point, the industrial design process looked a little like this:

The problem with this process was two fold—companies wouldn’t get feedback on their products until they went to market and many products that went to market did not meet user needs. This inefficiency led to the emergence of two new approaches: design thinking and user centric design. Industrial designers no longer built products for the sake of building them. For the first time ever, designers placed their emphasis on functionality, ensuring that human needs, pain points, and motivations were considered in the design process.

The 1970s and 80s saw the rise of companies like Apple and Xerox, who introduced the world to consumer digital products users could communicate and interact with. They were distinguished by their user interface, which allowed non-professionals access to the world of tech in a way never before seen.

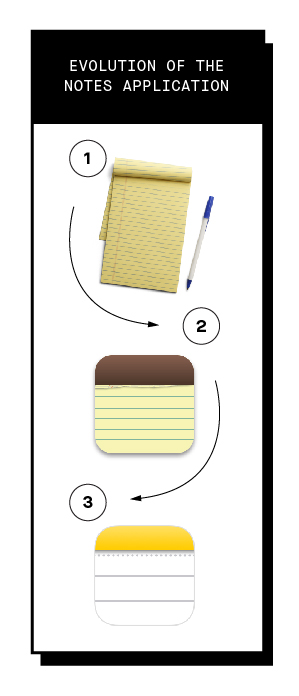

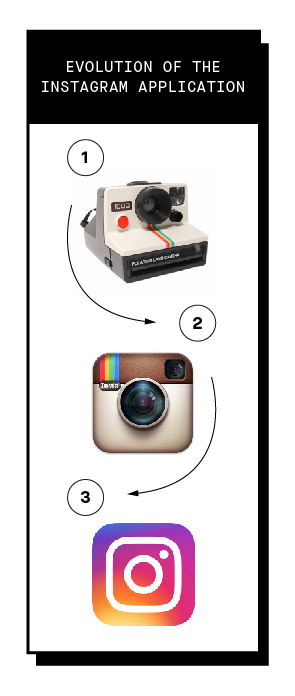

This was done by creating digital products that mirrored real world items—on early computers, you could get back to the home screen by clicking a button that looked like a house. Known as skeuomorphism, this style helped people understand how to use complicated products without explicit instructions.

Skeuomorphism played a large role in the design of digital products throughout the next two decades, including the design of the original iPhone. It wasn’t until 2013, when Apple released iOS7 that a new style—known colloquially as flat design—began to emerge. With flat design, user interfaces and iconography became more abstract. People no longer needed visual cues to understand how to use digital products.

Today, flat design still dominates but history shows that we shouldn’t expect that to last forever. In particular, conversation design, which describes digital products like Alexa and Google Home, could be a major disrupter. These products lack a user interface all together but still need to be designed intentionally to help solve problems.

Alexa: Let’s end this history lesson and go to the next section.

Digital products come in all shapes and sizes.

That website that you use to check your daily horoscope is a digital product.

That social media platform you use to keep tabs on your ex is a digital product too.

Even that weather app on your phone that never correctly predicts if it’s going to rain is a digital product, albeit not a great one.

So how do these digital products get made? Does it vary based upon the product?

Yes and no. While no two products are designed in the exact same way, product designers tend to follow a four-step process that looks like this:

First, they discover insight into a problem. They try to understand the cause of a problem and why current solutions aren’t currently working, For example, before Uber was Uber, the founders started with a simple question: why is it so hard to get a cab?

Next, they define an area of focus. Product designers begin to ask more specific questions to guide them toward an optimal solution. In Uber’s case, the founders were able to poke holes in the taxi industry model—allowing them to see an opening for a new, better solution.

Once a problem is well defined, product designers begin to develop potential solutions. This process is iterative which means that a product designer is unlikely to find the best possible solution on the first try. Most of the time, the best possible solutions come after testing and improving upon many suboptimal solutions. That is to say, for Uber, this was probably not their first attempt.

These first three steps enable product designers to ultimately deliver solutions that work. After months of hard work, a new digital product enters the market place. With the right marketing and timing, it could just revolutionize the way we've done something for decades.

Did you know? Just like that driver who went all out with lights and snacks, Thinkful has almost a 5 star rating! ★★★★★

Designing great products end to end is challenging, yet exciting work. To be successful, product designers need both a diverse set of skills and the ability to collaborate with many different stakeholders. On any given day, a product designer must understand UX, visual design, and front end design to move a project forward.

In the product design world, UX is often thought of as the “strategy” part of the design process. In order to build a product that will stick, you have to understand people and the challenges they face.

Product designers begin the process of discovery through qualitative research. This comes in many forms including 1-on-1 interviews, focus groups, and ethnographic research. For example, if a product designer was asked to build a new app for Starbucks, it would make sense that they would study and talk to Starbucks customers before doing so.

Collecting the right data from the right people is essential. That’s why product designers often use screeners to prequalify good candidates for interviews or focus groups. If you’ve ever encountered a product and wondered Why in the world did they build this?, there’s a good chance that the company didn’t follow proper data collection methodology.

UX research continues in the definition phase of product design. Here the product designer transitions to quantitative research in order to confirm or clarify insights they learned from the discovery phase.

For example, a focus group might indicate that users have a strong preference for using an email application on their phone rather than on a laptop. A product designer could then conduct a survey—a quantitative research technique—to understand if this is representative of the broader population.

Card sorting is another technique used during the definition phase. This allows the product designer to understand how users interact with information and the associations they make. Product designers might use card sorting to create a navigation menu at the top of a website. Or if they were building an app for a zoo, to figure out how people group animals.

Once the problem has been effectively outlined, it’s time to start brainstorming. This phase often kicks off with an exercise called crazy eights, which gives the designer 8 minutes to sketch as many solutions to the problem as possible. Also known as divergent thinking, this crucial step gets the creative juices flowing and allows solutions to emerge organically.

As soon as all the possible solutions have been identified, the product designer begins to test them. They start with wireframes (basically detailed sketches) of each solution and solicit feedback from users. Wireframes are tweaked based upon that feedback and tested many times over until a product designer can say with reasonable certainty which solution works best.

Digital products come to life in the deliver phase. Here, the product designer leverages their knowledge of visual and front end design to make a product that works as good as it looks.

Visual design is often described as taking the strategy from the first three phases and turning it into something tangible. It transforms the wireframe into something that looks, feels, and communicates like a real digital product. One of the most important steps in visual design is designing the product’s interface. This is how the product becomes “branded” and product designers spend their time thinking through the colors, typography, and verbiage of their product. The product designer might ask “should this product be young and playful or more buttoned up and polished?” Like the previous phases, they often test different design schemes with users to see what resonates best.

Front end design takes the static visual design and turns it into a functional product. Often times, those designs are handed off to a developer to code. However, product designers still need working knowledge of front end languages like HTML, CSS, and Javascript in order to give feedback, forecast timelines, and budget effectively.

Have you ever experienced a problem and thought, I wish there was an app for this. Or used a product that didn’t work effectively and thought there’s gotta be something better. Most of the time, this conversation with ourselves stops there because we don’t have skills to create that life-improving product.

That is until now.

If you are a great problem solver, then you can be a great product designer.

Contrary to popular belief, great product designers don’t need to be great artists. In fact, art and design are totally different things. While art is very subjective, design is objective. Design is about rules and defined processes with sprinkles of imagination.

Want to build the next video streaming service? Do it.

Have a great idea for a new social media platform? Now’s the time.

Dreaming of changing the world like Apple’s iPhone? There’s nothing stopping you.

Thinkful can help you learn product design and launch your career. To learn more about our flexible product design bootcamp, fill out the form below.

Keep Reading

Have your heart set on a different tech field? Read Part 1 of our WTF series to learn all about data science.

Acknowledgements

Images by Rachel Knobloch

Special thanks to Terry Million